KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Bond market’s reaction to Greek events has been muted so far and justifiably so.

- Key safety nets put in place by the European Central Bank and policymakers in recent years support limited bond market impacts.

- The growth trend continues to dominate long-term bond prices and yields despite unfolding Greek events.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

WHAT DO BONDS SAY ABOUT GREECE?

Bonds can be a leading indicator of financial markets and the global economy, and reaction to Greek events suggests limited concern. Yes, U.S. Treasuries prices rose strongly on Monday, July 6, 2015, in response to Sunday’s “no” vote in Greece rejecting the most recent offer from European institutions, including the European Central Bank (ECB). Both investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds underperformed Treasuries* for the day, following the typical script when investors see uncertainty and heightened risk. In Europe, the reaction was similar but perhaps more muted with the German 10-year Bund yield closing lower by just 0.03% while comparable maturity debt from Spain and Italy, the formerly troubled issuers, increased by 0.14% to 0.16%. European corporate bonds also witnessed modest price declines. The real damage occurred in Greece where the 10-year Greek government bond yield rose by a full 3 percentage points.

PUTTING IT IN CONTEXT

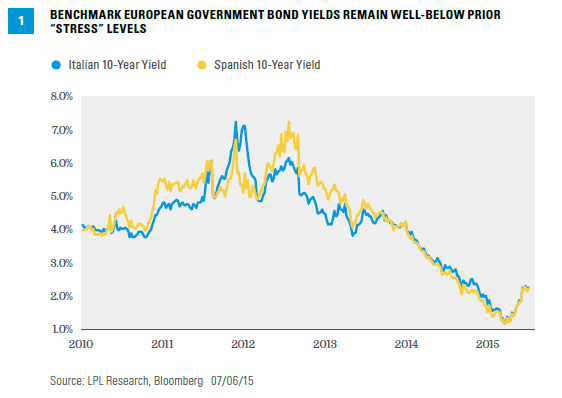

A look back over the two weeks ending July 6, 2015, reveals an even-tempered market. Benchmark 10-year yields in both Spain and Italy increased by 0.1%, while Portugal’s 10-year yield increased by 0.2%. The yield changes are relatively small given the increasing fears surrounding a potential Greek default. Furthermore, the absolute level of Spanish and Italian government bond yields remains very low compared with levels witnessed during the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent European debt scare in 2011 [Figure 1]. Keep in mind that the rise in Spanish and Italian government bond yields that began in mid-April 2015 had more to do with improving global growth prospects, which pushed government bond yields higher globally, than Greek fears, which have only recently influenced prices and yields.

The low overall level of Spanish and Italian government bond yields also reflects limited market concerns. Both Spanish and Italian 10-year government bond yields exceeded 7% during the peak of the European debt crisis. At times, these yields were similar or higher than those of the domestic high-yield bond market, implying a significant fear of default. Today, market fears of government default in both countries are extremely low as evidenced by yields of approximately 2.4% on Spanish and Italian 10-year government bonds (as of Monday, July 6, 2015), a far cry from 7%.

NO SIGNS OF BANK CONTAGION

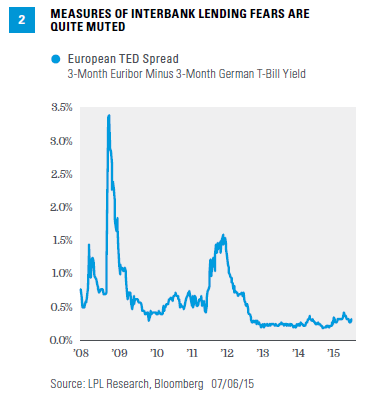

Interbank lending fears, a key early warning signal of the 2008 financial crisis, have increased but only marginally. The yield differential between the three-month Euribor (an interbank lending rate) and the three-month German T-bill remains modest compared with prior flare-ups of European debt fears [Figure 2]. The U.S. version of the same metric, known as the TED spread,** has only increased by 0.04% year to date through July 6, 2015. Signs that a Greek default or banking problems may spill over to other European banks and countries remain very limited. This is due to the limited amount of bonds held by financial market participants and the vast majority held by the ECB and IMF. (For more on Greece, see this week’s Weekly Market Commentary, “Greece Playbook,” and Weekly Economic Commentary, “The Fed After the ‘No,’” July 6, 2015.)

SAFETY NETS

Key safety nets are a big reason why market impact from Greece is likely to be limited. Related to the bank lending fears mentioned above, the ECB’s Targeted Long-term Refinance Operation (TLTRO), a bank lending facility to provide liquidity, remains largely unutilized. Current use of the ECB’s TLTRO is approximately €75 billion but it has a capacity of €375 billion. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is now fully operational and has a lending capacity of €450 billion if needed. Finally, last week the ECB added several corporate bond issuers to its list of eligible issuers for its bond purchase program known as quantitative easing (QE). By widening the pool of available bonds to purchase, the ECB increases its ability to fight off the spread of Greece-related debt fears across the Eurozone. These safety nets were gradually put in place in recent years and represent a key difference from 2008 and 2011, in addition to the improving economic growth witnessed across the Eurozone so far in 2015.

Greece’s missed IMF payment on July 1, 2015, creates a 30-day grace period, which provides room for further negotiation ahead of an important July 20, 2015, payment due to the ECB. On Monday, July 6, 2015, the ECB maintained its Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to Greek banks, but tightened the screws by stating that banks will have to post additional collateral to obtain cash. A missed payment to the ECB on July 20 would presumably lead to the end of ELA, forcing broad bank shutdowns in Greece-a step beyond current capital controls.

High-quality bonds may benefit as a result over the short term, although they have a long way to go to reverse the strength of more economically sensitive sectors such as high-yield bonds. The weakness in high-quality bonds has paused for now, but unfolding Greek events have so far only put a small dent in the growth trend that continues to dominate long-term bond prices and yields. We expect yields to ultimately finish 2015 modestly higher, as mentioned in ourMidyear Outlook 2015: Some Assembly Required publication, and for the challenging return environment to persist.

*As measured by the Barclays Corporate Index and Barclays High Yield Index compared to the Barclays Treasury Index.

**The TED spread is the yield differential between three-month London interbank offered rate (Libor) and the three-month U.S. T-bill rate.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values and yields will decline as interest rates rise, and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

Government bonds and Treasury bills are guaranteed by the U.S. government as to the timely payment of principal and interest and, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value. However, the value of fund shares is not guaranteed and will fluctuate.

Investing in foreign fixed income securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, political risk, and risk associated with foreign market settlement. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

High-yield/junk bonds are not investment-grade securities, involve substantial risks, and generally should be part of the diversified portfolio of sophisticated investors.

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS & DEFINITIONS

The Barclays Corporate Index is a broad-based benchmark that measures the investment-grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market.

The Barclays High Yield Index covers the universe of publicly issued debt obligations rated below investment grade. Bonds must be rated below investment grade or high yield (Ba1/BB+ or lower), by at least two of the following ratings agencies: Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch. Bonds must also have at least one year to maturity, have at least $150 million in par value outstanding, and must be U.S. dollar denominated and nonconvertible. Bonds issued by countries designated as emerging markets are excluded.

Quantitative easing (QE) refers to a central bank’s current and/or past programs whereby the bank purchases a set amount of Treasury and/or mortgage-backed securities each month from private banks. This inserts more money in the economy (known as easing), which is intended to encourage economic growth.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-398508 (Exp. 07/16)