KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Chinese government began to liberalize policies regarding the control of both the equity and currency markets.

- The markets have not always responded in the way predicted. The government responded by enacting additional policies, adding to volatility.

- Chinese economic problems are still mostly contained to China itself; spillover to other markets should be limited.

- Risks are elevated, especially since policy mistakes have shaken confidence in the Chinese government.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

CHINA: A ROCKY START TO A NEW (OLD) YEAR

Once again, the precipitous decline in the value of the Chinese stock market has spilled over to the broader global financial markets. The value of the Shanghai Index declined almost 15% since the beginning of the year, or at least the beginning of our year. China’s social and economic life is geared around the lunar New Year, which will be celebrated on February 8, 2016. The New Year makes a big difference in China, both psychologically and in real economic activity. Workers in China have seven days off and many travel home to visit family. In one week, years of migration from rural areas to cities is reversed, at least temporarily

Investors are revisiting issues last considered in August–primarily, the connection between China’s stock market and economy and the broader implications for the global economy. Our basic views on China remain consistent. China’s short-lived stock market bubble burst, but there is little connection between the market and the economy. China is undergoing a painful, but necessary, rebalancing of its economy away from strong government-led infrastructure and manufacturing-based development and toward a more consumer-led and service-based activity. We believe that China’s government still has the resources to smooth this transition. However, new risks are appearing. Many of China’s recent problems appear to be self-inflicted, caused by poorly designed or communicated government policies. China has taken steps to liberalize aspects of its financial markets without the intended result. We will detail some of these new policies and factors and how they may impact China, in addition to the rest of the world.

CHANGES TO EQUITY TRADING

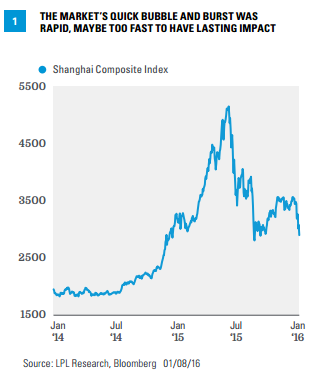

The Chinese government has engaged in a number of policies that have generally failed to have the intended effect. In April 2014 the government announced plans to create a Mutual Market Access (MMA) program, which allowed mainland Chinese investors to purchase stocks in Hong Kong and vice versa. This program was initiated with respect to the Shanghai exchange in November 2014, but has been postponed with the Shenzhen exchange due to market volatility. From July 1, 2014, to their peak on June 12, 2015, Chinese shares increased 150% [Figure 1]. Shares began to decline immediately thereafter. As this bubble began to burst, the government announced a series of measures to stem the decline in equities, including limiting short selling, forbidding certain insiders from selling shares, and halting trading in some stocks altogether. Some of these measures were by nature temporary and were set to expire at the beginning of this year. The government, through state-controlled companies and banks, the so-called “National Team,” began to purchase shares directly on the exchanges to support the markets. These measures were largely seen as counterproductive and lessened investor confidence in government actions. The Shanghai Composite fell 40% from its peak, though still ended 2015 up over 11%.

After January 1, 2016, the Chinese government instituted more rules to support the market, in part because some of the early restrictions were expiring. The most important was the introduction of “circuit breakers,” or the halting of trading should the market decline by more than 7%. During the first four trading days this year, these limits were hit twice, the second time within 30 minutes of the market opening. Trading was halted for the rest of both days. Before the market opened on Friday, January 8 (before the fifth trading day), this new circuit breaker rule was discontinued, but the other government policies remain intact.

Does this matter? Does the Chinese stock market reflect the reality of its economy, and how does it impact the overall economy? The evidence suggests that the links between the Chinese market and economy are tenuous at best. That is not to say that there are no connections, or that there will not be in the future, simply that those relationships are not strong today. China is largely a retail market, with 80% of trading coming from individual investors. Less than 10% of households in China own stock, compared with roughly 50% in the U.S., and many of those brokerage accounts were opened during the runaway market of early 2015.

The Chinese market is generally not viewed by Chinese people as a place to store and build wealth. Rather, it is a place to speculate. Chinese households maintain less than 10% of their total wealth in stocks.

Why Do Circuit Breakers Cause Volatility?

Circuit breakers and similar mechanisms are designed to allow investors and traders an opportunity to evaluate the market and avoid panic. Yet, they can have the opposite impact. Why? Should the market fall, traders worry that the circuit breakers will be tripped, which would prevent them from selling in the future. This encourages traders to sell first, and evaluate later. Given that every trader has effectively the same choice, rational traders sell early, creating the situation that makes hitting the breaker more likely.

Does the U.S. Stock Market Have Circuit Breakers?

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) has circuit breakers at 7%, 13%, and 20%; however, the first two only halt trading for 15 minutes, and after 3:25 p.m., trading will not be halted at all. Only a 20% decline before 3:25 p.m. would cause trading to halt for the rest of the day.

CHANGES TO CURRENCY POLICY

Another source of concern stemming from China is both the devaluation of the yuan and the reduction in Chinese foreign currency reserves.

Renminbi vs. Yuan

China makes a distinction that no other country uses. The word “renminbi” is the name of the currency, literally meaning “the people’s currency,” and “yuan” is the word used when giving the amount. The bill may be 100 yuan, payable in renminbi. In practice, the two are used interchangeably; official documents use the proper terms. At LPL Research we use “yuan” but may cite sources that use “renminbi” to be as accurate as possible.

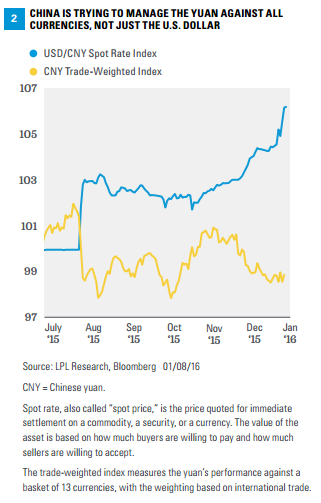

China has long desired to be a true power in international trade and finance, not simply a source of cheap manufactured goods. It has taken a number of steps to “globalize” its currency and financial system. This desire is why the inclusion of the yuan in the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights (SDR) program was so important to China. Yet, at the same time, and in complete contradiction, the government still attempts to maintain some control over the market. Figure 2 shows the performance of the yuan against the dollar, but also against China’s other major trading partners. As this figure shows, the question of whether the yuan is appreciating or depreciating is not a simple one.

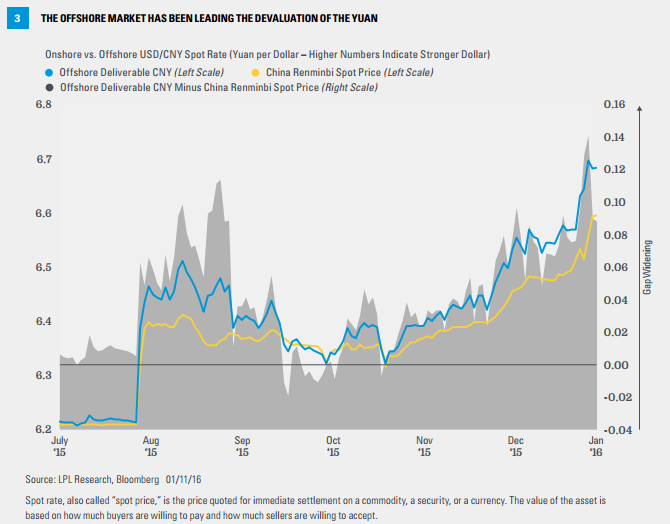

The Chinese government has tried to orchestrate this seemingly impossible goal of a global currency controlled by the government by allowing two currency markets. It created an “offshore” currency market by striking deals with banks, initially in Hong Kong, but more recently in Singapore, London, and other major offshore banking sectors. The Chinese government has created the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) program and has also engaged in swap agreements with the central banks of those countries. These programs are designed to allow for international trade to be conducted directly in the yuan. This trade sets the value of the yuan against the dollar and other major currencies.

The Chinese government has another system for determining the value of the yuan, the “onshore” system, which is run by banks located in mainland China. This system has changed dramatically over the past six months. Originally, the opening rate was “fixed” by the government based solely on the yuan/U.S. dollar exchange rate and then was allowed to move as much as 2% in either direction. However, the Chinese government liberalized this system last year by using market prices for the daily “fixing.” The government also uses multiple currencies, not just the U.S. dollar, to manage exchange rates. Both changes are consistent with China’s goal of having a globally accepted currency.

However, Figure 3 shows the more recent problem. The free market exchange rate is pushing the value of the yuan lower against the U.S. dollar, motivating the Chinese government to allow further devaluation. This is often decried in the U.S.; but it is really not the government that is devaluing the currency–the government is now finally paying attention to market forces.

The short-term outlook for the yuan versus the dollar continues to be negative. Mainland investors are looking to diversify their holdings. Should the Shenzhen-Hong Kong MMA become reality, it could result in net sales of the yuan. China is also spending yuan to shore up infrastructure in other parts of Asia in order to more easily facilitate trade of goods. The willingness of Chinese citizens to buy property in the U.S. and Canada also reflects this desire for diversification.

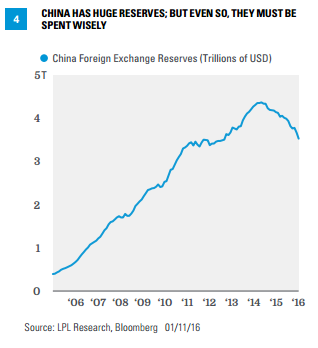

The Chinese government had been fighting to maintain a higher yuan, or at least control its decline. Figure 4 shows Chinese massive currency reserves, which are its real source of strength should the government need to inject capital to strengthen the economy. Even though these resources are huge, China has been spending some (roughly $140 billion in December alone) to support the yuan. While China has given the market some transparency into the tactics of its involvement in the currency market, it has been unable to articulate a definitive strategy, or at least one the market is willing to accept.

Either a highly volatile yuan or a steadily falling one would be contrary to China’s long-term goals of having its currency widely accepted. As with its liberalization of the equity markets, the government appears displeased with the result of allowing greater flexibility and freedom in the financial system.

CONCLUSION

Chinese leadership has made a difficult situation (the rebalancing of its economy) worse by poor policy decisions and communications. China’s stock market is still not a major factor in consumption decisions and there seems to be very little “wealth effect” in China. Yet the government’s poor handling of both the boom and bust calls into question its basic competence. The same is true for its communication around currency issues. China either needs to clarify its policy, or explain how the current policies can be made consistent with each other. These policy errors are eroding global confidence that the Chinese government has what it takes to handle its main task–the rebalancing of its economy.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing.

All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. Any economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Investing in stocks includes numerous specific risks, including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal, and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

Investing in foreign and emerging markets securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, geopolitical risk, and risk associated with varying accounting standards. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

Currency risk is a form of risk that arises from the change in price of one currency against another. Whenever investors or companies have assets or business operations across national borders, they face currency risk if their positions are not hedged.

INDEX DEFINITIONS

The Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index is a capitalization-weighted index. The index tracks the daily price performance of all A shares and B shares listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The index was developed on December 19, 1990 with a base value of 100. Index trade volume on Q is scaled down by a factor of 1000.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial LLC is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-455754 (Exp. 01/17)