KEY TAKEAWAYS

- European integration has been increasing steadily since the end of WWII.

- The U.K. is renegotiating its membership in the EU.

- The U.K. leaving the EU–the “Brexit”–would support anti-EU sentiment in other countries.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

POLITICS, ECONOMICS, AND THE BREXIT: TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Heads or tails, politics or economics? Politics and economics are separate, but related disciplines, like two sides of the same coin. In an attempt to ensure that the continent would never suffer another major conflict after World War II, Europe embarked on a movement toward both political and economic integration. At times there have been disagreements, but as a whole, the European experiment–viewing Europe as a single economic and political entity–has moved forward. The United Kingdom has negotiated changes to its membership in the European Union (EU) that will be voted on by EU member nations on February 18, 2016. As early as June of this year, the U.K. will hold a referendum on whether it should leave the EU, an act referred to as the “Brexit.” Other populist anti-European movements are growing and will no doubt be influenced by the EU’s response to the U.K.’s request and the proposed June referendum.

THE MOVE TO INTEGRATE

The movement toward European integration began after World War II. After two major wars in three decades, European leaders were determined not to allow a third. In addition, the beginning of the Cold War and the creation of NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) in 1949 required western European countries to focus their attention on the Soviet Union. In 1951, the first pan-European organization, the European Steel and Coal Commission, was created to coordinate steel production. French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman said this would make war between France and Germany “not merely unthinkable but materially impossible.”

The next wave for European integration was focused on economics. Over several decades, common trade policies were created, most importantly the creation of a “customs union” in 1968. In a customs union, not only is there unfettered trade within the member countries, but the countries agree on a common tax regime for goods coming in from outside the region. This move has significant political ramifications as countries give up a major right of sovereignty, the ability to control all trade at their borders, not just trade from members.

Though the U.K. first applied for membership in 1961 in what was then called the European Economic Commission, it was not granted membership until 1975, after the U.K. held a referendum following its request for concessions from the other members. The current negotiations are not the first time the U.K. has sought exemptions from certain EU provisions.

Whether due to language, culture, or simply the amount of time the U.K. spent outside of the EU, the political culture in Britain never embraced “Europe” as a political entity. Though the English Channel is only 21 miles wide, to the British it must look like an ocean. This skepticism is not just a function of geography or history; Scotland is far more pro-European than Britain.

The other major economic milestone for political Europe is the creation of the euro, and the removal of national currencies. This is perhaps the ultimate surrender of national sovereignty. With two exceptions, all members of the EU must ultimately accept the euro; currently 19 of the 28 EU members use the euro (collectively known as the Eurozone). Six of the remaining nine are Eastern European nations deemed not ready for adoption. The U.K. and Denmark negotiated an exception to the mandatory use of the euro. Sweden refuses to accept the euro on what amounts to a technicality, though the EU has allowed this to go largely unchallenged.

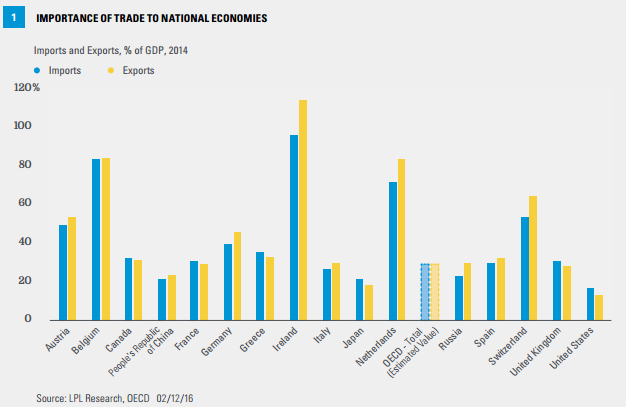

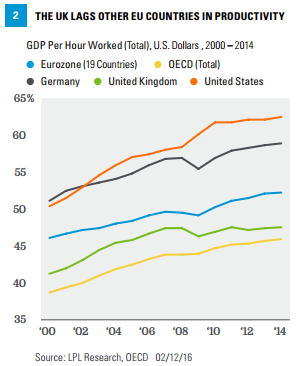

Where does this leave the U.K. economically? Two things stand out. First, the U.K. is less dependent on trade than any other major country in the EU [Figure 1]. Second, the U.K. lags the rest of Europe in terms of productivity when measured by gross domestic product (GDP) per hours worked [Figure 2]. U.K. politicians in favor of leaving the EU will often point to regulations foisted on its economy from the EU as limiting economic growth. That may be true, but it does not put the U.K. at a competitive disadvantage relative to other countries in the EU. The U.K. decided to retain its currency and a level of sovereignty. However, when compared to other higher economically developed economies in the EU, it appears that it may have forgone an economic benefit by not accepting the euro.

MORE THAN ECONOMICS

Whatever one thinks of the results of the economic integration of Europe, it is the political issues, especially those that involve national sovereignty, that are causing nations to consider reversing course. The most emotional issue involves immigration and the free movement of people within the EU borders. In fact, the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP) lists immigration first when it mentions “the issues of the day” on its website, before the economy, healthcare, and living standards.

In 1985, several European nations agreed to the Schengen Treaty, which allowed people to travel freely (without passports or further controls) with its region. This treaty was expanded over the years to become a core feature of the EU, to which all members must fully accede. Again, the U.K. (along with Ireland) was granted some exemptions from the requirements.

Immigration to the U.K. has averaged from 500,000 to 600,000* between 2006 and 2014. Official statistics are unavailable for 2015, but are probably near 700,000. The number of people coming to the U.K. from within the EU and those coming from outside of it are approximately equal. Refugees from the wars and political unrest in Syria, Libya, and other North African nations have been adding to the migration pressures. The U.K. wants greater ability to handle the immigration issues. This means limiting entrance, enforcing residency requirements before social services are offered, limiting citizenship by marriage to prevent fraud, and other similar measures. Current EU rules limit, if not expressly prevent, the U.K. from enacting these sorts of rules.

Though immigration tends to grab headlines, there are three other issues of contention, including:

- Economic governance. The U.K. is not part of the Eurozone, yet London operates as the European financial capital. The David Cameron government is concerned that countries in the Eurozone will pass regulations that will reduce the competitiveness of U.K. banks, and U.K. companies in general. It wants assurances that the countries not using the euro will not be discriminated against. In addition, it wants assurances that U.K. regulators will remain the primary regulator of U.K. financial institutions.

- Economic competitiveness. The U.K. would like to see a relaxed regulatory burden on all businesses. Though this seems a simple and obvious request, it is made difficult by the fact that the EU is comprised of 28 different nations. One nation’s view of onerous regulation is another’s guarantor of social harmony or environmental sensitivity.

- National sovereignty. EU and Eurozone nations have given up so much in the way of national sovereignty, most notably their currencies and the right to control their borders. Yet EU documents still maintain an obligation to an “ever closer union.” The U.K. would also like to see an increased role for national parliaments. Effectively, the U.K. would like a declaration suggesting that the period of integration has ended for the foreseeable future.

The European Council of national leaders has partially addressed the U.K. concerns. It is now up to both national leaders and the British people to decide if the compromises announced on February 2 are acceptable. Polling data in the U.K. suggest that support for the Brexit is growing, and may happen regardless of the results of this week’s meeting.

Timeline of Events

- January, 2013. U.K. Conservative Party Prime Minister David Cameron promised to renegotiate the terms by which the U.K. is a member of the EU, and hold a national referendum on whether those new terms would be satisfactory.

- May 7, 2015. The U.K. held its general election. The result was a resounding victory for the Conservative Party, suggesting a high degree of support for the renegotiation, if not support for leaving the EU altogether.

- February 2, 2016. The European Council announced a draft renegotiation of the U.K.’s membership in the EU.

- February 18 - 19, 2016. Expected vote of European leaders on proposal.

- June 2016. Expected referendum in the U.K. on continued membership.

- October 2016. Spanish regional elections. Separatists in the Basque region look to the U.K. independence movement as granting legitimacy to their attempted devolution from Spain.

- 2017. Original time frame for U.K. referendum.

IMPLICATIONS OF A BREXIT

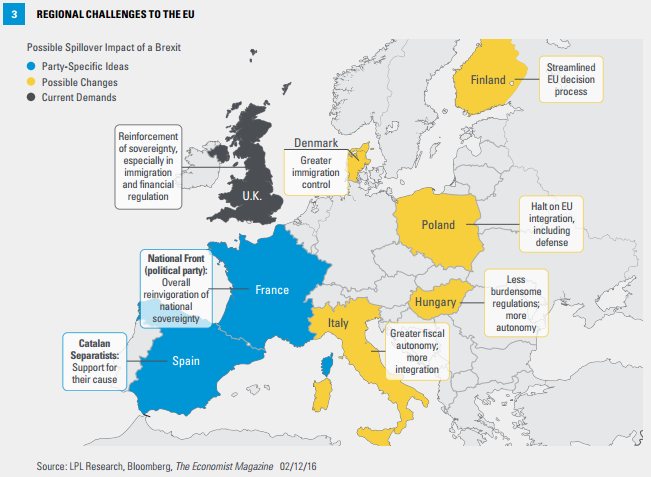

The implications of a Brexit are both political and economic, with little real consensus regarding a final conclusion. From a political perspective, the biggest implication would be the tacit support for other anti-EU movements across the continent. Figure 3 shows a map of the region, highlighting national movements that support increased autonomy for countries or regions.

The debate over the economic impact of a Brexit is highly partisan. However, some non-partisan groups have studied the matter in detail. A group from the London School of Economics suggests that the U.K. would suffer a loss of GDP between 1.1% and 3.1% due to a reduction in trade. In the long run, this group suggests that U.K. productivity would slow, which is particularly important given its economy is already less productive than peers (as shown in Figure 2). In addition, the U.K. would be forced to negotiate any further trade agreements on its own, rather than as part of the EU. This could leave the U.K. unable to further its interests. Of course, the UKIP and similar parties dispute these and similar viewpoints expressed by mainstream analysts.

Perhaps the biggest wildcard is what would happen to London as a banking center. One factor in the renegotiation is London’s protection. If London is not safe given the U.K.’s current status, it must be considered less so should the Brexit occur.

CONCLUSION

“Europe” as a concept, rather than a just a place, is facing a critical test this week, and throughout this year. The benefits of economic integration appear clear. If anything, the data suggest that the U.K. might even benefit from increased economic coordination. However, politics matter in ways that do not show up neatly on national accounts and mathematical models. It is not for us to say how either side should decide the issues before them. That said, in our view, the possible reversal of a 75-year trend toward integration and harmony will have negative ramifications. We also cannot ignore the rising tide of populism, both in the U.S. and Europe, and question whether this tide will not overwhelm more sober economic calculation. At this point, it looks like both sides are flipping the coin hoping it lands on its edge, a most unlikely outcome.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Investing involves risk, including loss of principal.

Investing in foreign and emerging markets securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, geopolitical risk, and risk associated with varying accounting standards. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments, and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-468578 (Exp. 02/17)