KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The December 2015 FOMC meeting is a “live meeting,” suggesting that a rate hike cycle could begin for the first time in nearly 12 years.

- Two more jobs reports, as well as reports on inflation and the labor markets, will be watched closely between now and the December meeting.

- Fed officials may be lowering the bar for the target job count number that would signal “further improvement in the labor market.”

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

LOWERING THE BAR?

Last week (October 26-30, 2015,) the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) policymaking arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), met for the seventh time this year. As expected, they made no change to monetary policy. However, the statement released after the meeting caught many market participants off guard, reminding them that the next FOMC meeting on December 15-16, 2015 is a “live meeting,” suggesting that the FOMC could start a rate hike cycle for the first time in nearly 12 years as soon as next month.

Prior to the October 28, 2015, FOMC meeting, market participants–as gauged by the fed funds futures markets–didn’t think the Fed would raise rates until the middle of 2016. Our long-held view remains that the Fed will begin to raise rates in late 2015 or early 2016, and that it will raise rates three or four times, by 25 basis points (0.25%) each, by the end of 2016. The Fed itself is saying it will do five or six 25-basis-point hikes, while markets expect just two 25-basis-point hikes next year.

Of course, it’s not a foregone conclusion that the Fed will raise rates in mid-December 2015 and Fed officials continue to stress that the first rate hike–and any hikes thereafter–are data dependent. The October 2015 FOMC statement included a summary of the key criteria:

“The Committee anticipates that it will be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it has seen some further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term.”

WHAT DEFINES “FURTHER IMPROVEMENT”?

Garnering the most attention and discussion from the above statement is the phrase, “some further improvement in the labor market.” The October 2015 jobs report is due out this Friday, November 6, 2015, and is one of two jobs reports due out between now and the final FOMC of 2015. In light of the October 2015 FOMC statement that keeps the December 2015 FOMC meeting in play, market participants will be closely watching the economic data–and especially the reports on inflation and the labor markets–closely over the next six weeks. This week, as market participants digest the October jobs report, they will be asking: What exactly does “some further improvement in the labor market” look like?

The consensus of economists as polled by Bloomberg News expects that the U.S. economy created 180,000 jobs in October 2015 and that the unemployment rate–derived from a survey of households–will fall to 5.0% in October 2015 from 5.1% in September 2015. And while the 180,000 increase in jobs expected by the consensus appears to be a marked downshift from the average of 229,000 jobs created each month over the past 12 months, a quick review of recent comments from Fed officials suggests that a gain of 180,000 is well above what many FOMC members consider “some further improvement” in the labor market. This disagreement–one of many between the Fed and the market–bears watching in the coming weeks and months as the Fed begins to normalize policy.

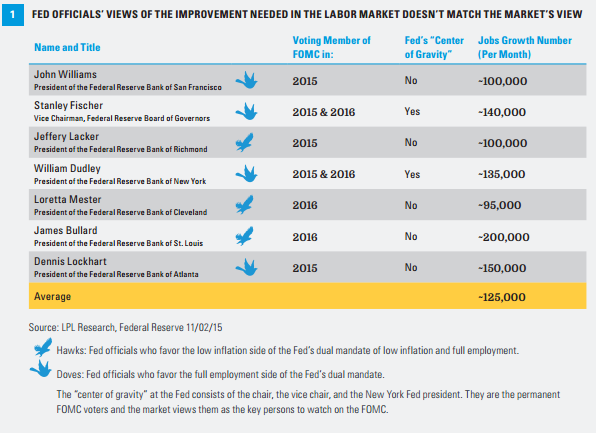

During the month of October 2015, several key members of the FOMC made public appearances in which they made specific comments on the pace of job creation in the U.S. economy as it relates to Fed policy, helping market participants decipher what exactly “some further improvement in the labor market” means in terms of the monthly job count [Figure 1]. On balance, comments from those members put the monthly gain in payroll jobs necessary to tighten the labor market at around 125,000 net new jobs per month.

The comments on the pace of jobs creation needed to sustain the improvement in the labor market came from both policy hawks (those who favor the low and stable inflation side of the Fed’s dual mandate) and doves (those who favor the full employment side of the dual mandate). The comments of John Williams, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, a policy dove, and a voting member on the FOMC until the end of 2015, are especially instructive. In a speech delivered on October 8, 2015, Williams said:

“The pace of employment growth, as well as the decline in the unemployment rate, has slowed a bit recently…but that’s to be expected. When unemployment was at its 10 percent peak during the height of the Great Recession, and as it struggled to come down during the recovery, we needed rapid declines to get the economy back on track. Now that we’re getting closer, the pace must start slowing to more normal levels. Looking to the future, we’re going to need at most 100,000 new jobs each month. In the mindset of the recovery, that sounds like nothing; but in the context of a healthy economy, it’s what’s needed for stable growth.”

It’s notable that Williams, a dove, has set such a low bar for job creation. On the other end of the policy spectrum, James Bullard, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, a policy hawk, and a voting member of the FOMC in 2016, put the job count number closer to 200,000 per month. Normally, you would expect policy doves to have higher thresholds for job creation than policy hawks, so the fact that both hawks and doves have lowered the bar is telling. In remarks to reporters in early October 2015, Bullard said that sub-200,000 per month job gains “will become normal” in the next couple of years.

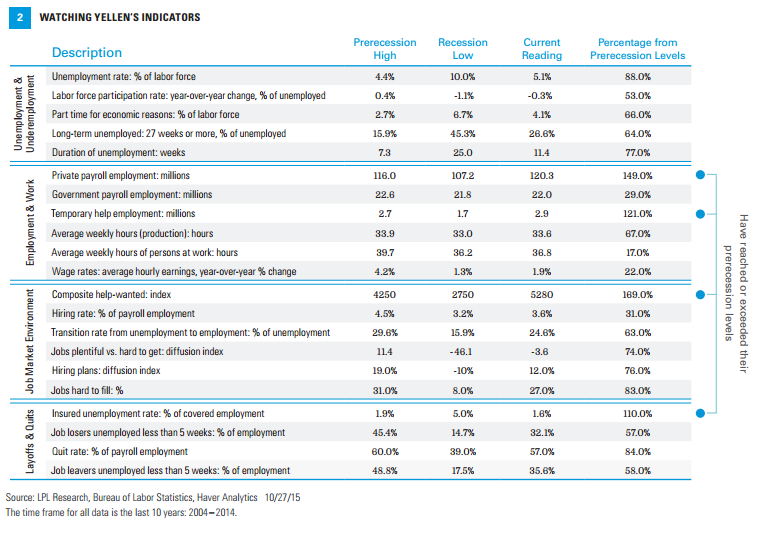

While a broad range of Fed officials put the target job count number at around 125,000 per month, the most important member of the FOMC, Fed Chair Janet Yellen, remains reluctant to be specific about the pace of job creation she is targeting. Instead, Yellen continues to say the Fed is looking at a wide range of indicators on both the labor market and inflation as it contemplates its next move [Figure 2]. On balance, while the Fed won’t just look at the nonfarm payroll count to gauge whether or not it raises interest rates, there seems to be a great deal of disagreement between what many Fed officials think is the key number on jobs and what the market thinks that number is. We will be watching this disagreement–one of several items that the Fed and market are at odds over–closely, as the Fed begins to raise rates for the first time in 12 years.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide or be construed as providing specific investment advice or recommendations for your clients. Any economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Investing in stock includes numerous specific risks including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-435985 (Exp. 11/16)