KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The challenges produced by bouts of illiquidity have always been a characteristic of the bond market and are not going to fade away.

- Lesser liquidity poses two primary risks: more volatile price movements and greater swings in lower-rated or more economically sensitive bonds.

- We disagree with some of the current apocalyptic scenarios and bouts of illiquidity can provide opportunity.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

AGONIZING OVER LIQUIDITY

Liquidity, or lack of it, continues to stir up fear for bond investors. Last week, negative headlines about bond liquidity increased and, separately, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed new rules for bond liquidity. Liquidity is likely to be an ongoing challenge in the bond market, more so for certain sectors than others.

Liquidity is the oil that lubricates financial markets and is particularly important in the bond market where trading is not done on a major exchange. The over-the-counter nature of the bond market requires two parties to agree on price for each transaction. A lack of willing participants to make markets in a specific security or segment of the market leads to illiquid trading, which can exacerbate price weakness even if the intrinsic fundamental value of a security may not have changed. If a buyer views an investment as possibly difficult to sell, a lower price may be demanded up front to compensate for the potential future difficulty. This is particularly evident during periods of volatile markets, like now, when many investors may try to avoid risk and shift focus to the highest-quality, most liquid securities in the market. Corporate bond markets, particularly high-yield bonds, have been hampered recently by less liquid markets, but this is common during periods of market turmoil.

Liquidity

Liquidity is the ease with which an investment can be bought or sold. The larger and higher quality the market, the greater the liquidity, and vice versa. Housing is considered an illiquid investment because it typically requires weeks or months to sell a home, whereas most stocks and bonds can be bought and easily sold on a daily basis.

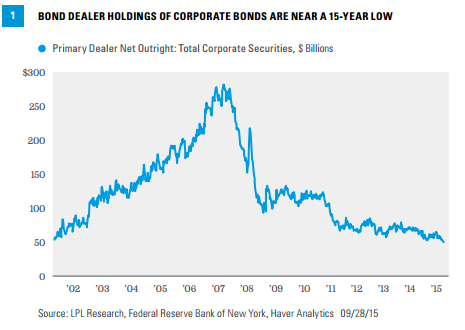

Liquidity, or lack of it, has become a greater risk in recent years as big banks, traditional large-scale players in the bond market, have gradually reduced their market participation. Due to Dodd-Frank financial regulation, financial institutions have less incentive to maintain an inventory of fixed income securities and warehouse certain types of bonds. Not only are bond dealers holding fewer bonds, but they are incentivized, via regulation, to hold higher-quality bonds such as Treasuries. The inventory of corporate bonds held by bond dealers remains near the lowest levels since the end of the financial crisis [Figure 1].

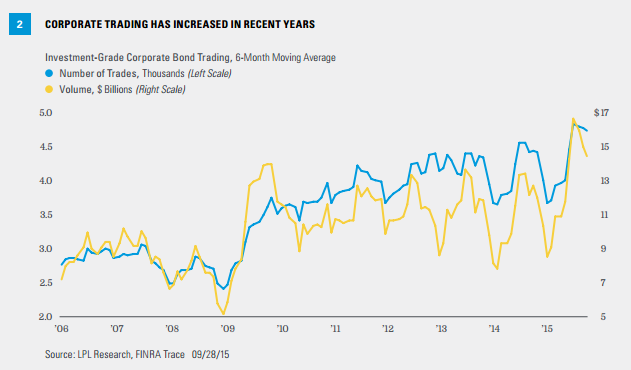

However, these same primary dealers have adapted by becoming more efficient, while smaller dealers, along with the emergence of electronic platforms, have arisen to partially fill the gap. Both the number and volume of investment-grade corporate bond trades have increased in recent years [Figure 2]. The increase in trading and volumes is rarely cited and actually improved both for investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds in recent years.

Growth in the corporate bond market since the end of the recession does diminish some of the impact of increased trading activity. Additionally, we still see less activity from large scale players, which could pose challenges. According to FINRA data, the number of “block” trades of $5 million or more has steadily declined since 2006, with the average dollar amount of those trades also falling, suggesting fewer trades by traditional market makers that help anchor the market.

NEGATIVE HEADLINES & THE SEC

Still, this does not justify some of the more negative headlines in our view. For example, a recent story focused on how many days it might take to liquidate a certain quantity of a single bond issuer based on how frequently it has traded. A substantial portion of bonds do not trade everyday like stocks. If a desirable bond issue has not traded in some time, this does not necessarily make it illiquid. This is exactly the case with many older, higher-quality, higher-income-generating bonds. If such bonds were to be sold, they may trade very quickly even if they have not traded in months, or years, as the case may be with certain municipal bond issues.

The SEC has proposed minimum liquidity holdings and/or additional charges for redemptions above a certain threshold during volatile markets. While both may have been driven by good intentions, the proposals are not ideal. The potential rules up for discussion may water down investment exposure or simply discourage investment.

So what does lesser liquidity mean? Two risks are highlighted:

- More volatile price movements. In illiquid markets, price swings can be exacerbated both to upside and downside. Liquidity works both ways. During illiquid markets, bid-ask spreads often increase and may result in poor execution, which also works to exaggerate price moves. Riding the downturn can be painful, but for those with cash to put to work, illiquid markets can offer opportunity.

- Greater swings in lower-rated or more economically sensitive bonds.Lower-rated bonds, such as high-yield bonds, are among the bonds most influenced by liquidity conditions. Due to their potential default risk, high-yield bond prices and yields usually incorporate some liquidity considerations as they may be difficult to sell during times of market stress.

PRIOR EXAMPLES

So, how might bouts of illiquidity impact investors? A look back at prior episodes may provide some perspective:

- The Treasury flash crash. On October 14, 2014, the 10-year Treasury fluctuated in an astounding range of 0.34% in a single day, one of the largest intraday swings on record. Within a seven-minute span, the 10-year Treasury yield dropped by 0.30% before quickly rebounding and finishing the day lower by 0.06%. An investigation into trading patterns found no single cause, but intraday volatility was spurred by illiquid markets. Evidence of illiquid conditions in the Treasury market this past spring contributed to Treasury weakness from late April to the end of June.

- The taper tantrum. From May 2013 through early September 2013, the bond market witnessed one of the sharpest and quickest sell-offs in history, as measured by the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Illiquid trading conditions exacerbated price declines. The sell-off originated in the high-quality bond market in response to bond purchase “tapering” by the Federal Reserve (Fed) but spread to other sectors including high-yield. The downdraft in high-yield brought in buyers and enabled that market to stabilize in July before stability ultimately returned to high-quality bonds. Once again, the market overshot and 2013 weakness reversed in 2014.

- The Whitney flu. This was caused by comments from analyst Meredith Whitney that a deluge of municipal bond defaults would plague the municipal bond market in late 2010 and early 2011. Default fears combined with a new issue supply surge hammered municipal bond prices. Ultimately, high-quality municipal bond prices would recover losses and more during the remainder of 2011 and into 2012. For investors buying into the weakness, misplaced fear provided a great opportunity.

- The 2008 financial crisis. Easily the most illiquid market investors have witnessed in many decades. We strongly believe that such a scenario is highly unlikely to unfold; but during this period, prices of high-yield bonds and other lower-rated issues fell drastically. In early 2009, market-implied default expectations on high-yield bonds over the coming 12 months reached nearly 25%. It would have taken strong conviction to buy, but the high-yield default rate peaked at 13%. The market overshot. For investors that held through the downturn, high-yield bonds recouped their losses and more.

The challenges produced by bouts of illiquidity have always been a characteristic of the bond market and are not going to fade away. At times the impact is greater than others. For some it can be frustrating, but trying to exit such positions during downdrafts may not be prudent and could do more harm than good. Some of the more dire scenarios painted by news stories seem to lose sight of the larger perspective, in our view; and for investors who are able, bouts of illiquidity can provide opportunity.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values and yields will decline as interest rates rise, and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

Government bonds and Treasury bills are guaranteed by the U.S. government as to the timely payment of principal and interest and, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value. However, the value of fund shares is not guaranteed and will fluctuate.

Investing in foreign fixed income securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, political risk, and risk associated with foreign market settlement. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

High-yield/junk bonds are not investment-grade securities, involve substantial risks, and generally should be part of the diversified portfolio of sophisticated investors.

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS

The Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based flagship benchmark that measures the investment-grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market. The index includes Treasuries, government-related and corporate securities, MBS (agency fixed-rate and hybrid ARM pass-throughs), ABS, and CMBS (agency and non-agency).

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-425013 (Exp. 09/16)