KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The referendum result this weekend throws Greece’s future in the currency union firmly in doubt.

- Here we address the question of whether the heightened risk of a Greek exit from the Eurozone might lead to contagion for global markets.

- We do not believe Greece is another “Lehman moment” and it may present an attractive buying opportunity for European equities.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

GREECE PLAYBOOK

Greece’s critical referendum took place this weekend and the Greek people resoundingly voted “no”–rejecting the latest bailout deal from creditors. The referendum result, which some interpreted as a vote to exit the Eurozone, throws Greece’s future in the currency union firmly in doubt. The unexpected result has led to a roughly 2% decline in the broad European indexes but only a modest decline in the S&P 500 (as of 3 p.m. ET today, July 6, 2015). The negative market reaction in Europe is not surprising, given polls heading into the weekend suggested a vote for the bailout was more likely. The modest decline in the U.S. may suggest markets are increasingly comfortable with the situation.

Here we try to answer the following questions:

1. Would a Greece exit (Grexit) from the Eurozone lead to contagion for global markets?

2. Will this latest Greece crisis result in a Lehman moment?

3. Is a deal that keeps Greece in the Eurozone still even possible?

4. Does anticipated weakness in European equity markets present a buying opportunity?

We address these questions here and provide our playbook for investing in this environment.

ASSESSING CONTAGION RISK

We know the stock market does not like uncertainty, so the prospects of Greece’s exit, which is now potentially greater than a 50% probability, are unsettling. No country has ever left the Eurozone, and there is no blueprint for how to do so. As we list below, there are several reasons why we expect the risk of contagion to be manageable.

Little private ownership of Greek debt. More than 80% of all Greek government debt is held by government agencies and central banks. Given how little Greek debt is held by private investors, we believe the global financial system should be able to manage prospects of Greece defaulting on additional obligations (the next payment is 3.5 billion euros due to the European Central Bank [ECB] on July 20). Derivatives exposure tied to Greek default cannot be precisely measured; however, we know banks are much better capitalized than they were when the Greek debt crisis bubbled over in 2012, and the data we do have for the banks suggest exposure is limited.

Bold ECB. The ECB’s willingness to “do whatever it takes” to keep the Eurozone together, and its aggressive bond buying program–which it can accelerate–suggest that it will step in to stem any signs of contagion. Should Greece’s problems remain simply Greece’s problems, the Greek crisis will be contained. Regardless of the path Greece takes, we expect the ECB could be very aggressive to ensure that markets beyond Greece continue to function as normally as possible.

Improved European economic backdrop. The European economy has been strengthening. European exporters, particularly Germany, have benefited from the weaker euro currency. The Eurozone’s 52.5 reading on its Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for June 2015 was the highest in four years and suggests the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) program is working. Private sector loans in the Eurozone are growing (1.2% year over year in May 2015) for the first time since 2012. Add to that the fact that the Greek economy, at less than 2% of the Eurozone’s gross domestic product (GDP), is too small to have any meaningful impact on the global economy other than through its potential ripple effects on broader financial markets.

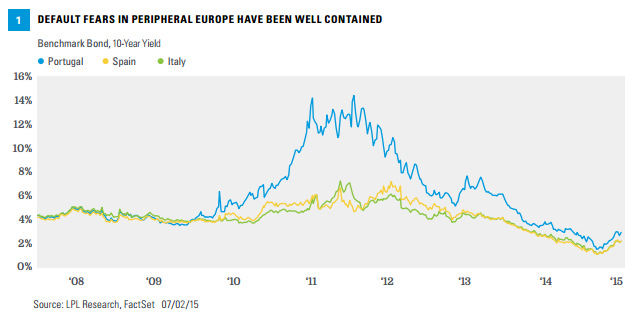

Improved conditions in peripheral Europe. Italy, Spain, and Portugal–where potential contagion risks are centered–have come a long way since the European debt crisis reached a boiling point in 2012 (when Greece previously defaulted). Each of those countries saw a year-over-year increase in GDP during the first quarter of 2015 (as did all Eurozone countries). Each is running a current account surplus, so they are not heavily dependent on external financing.

Bond markets in these peripheral European countries have been relatively calm even right up until the referendum vote [Figure 1]. These yields are likely to rise as a result of the latest increased risk of global market disruption, but economic improvements may help limit the magnitude of the sell-off in these bond markets. In fact, perhaps counterintuitively, the Greek situation may actually provide impetus for these countries to make the necessary structural reforms to head off more dire consequences later.

These factors do not mean financial markets may not weaken as a result of heightened risk if Greece leaves the Eurozone, but we do believe they point to markets stabilizing in the coming weeks.

WILL GREECE BE A LEHMAN MOMENT?

Greece is not another Lehman moment. Lehman was very different in terms of its leverage and the breadth of its exposure across the financial system. The Greece situation is of course still fluid, but regardless of which path Greece takes, we do not believe its latest crisis will lead to the end of the U.S. economic expansion or the bull market. For the reasons discussed above, we see the risk of contagion in global markets as manageable and we expect the impact to be relatively short term. Even Greece’s potential exit from the Eurozone may only have limited ripple effects given the years that central banks, regulators, private business, and investors have had to prepare for this drawn-out, but inevitable, outcome.

IS A DEAL STILL EVEN POSSIBLE?

The odds of a Greek exit from the Eurozone are certainly higher following the referendum result. European leaders remain very skeptical regarding Greece’s trustworthiness as a negotiating partner; the referendum only strengthens the position of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and the Syriza party. Negotiations will remain tough.

But a deal could still happen. Reports out of negotiations last week suggested the two sides were close. The Greek government wants to stay in the Eurozone and polls have consistently indicated the Greek people feel the same way. Ahead of the referendum vote, Tsipras argued for his position by telling the Greek people that a “no” vote would strengthen their negotiating position to secure a better deal with creditors (the so-called Troika of the International Monetary Fund, ECB, and European Commission). Tsipras already stated, very shortly after the vote, that he intends to return to the negotiating table. Even though the vote was considered a victory for him, Greek Finance Minister Varoufakis resigned shortly after the result was announced. Perhaps a less combative negotiator will be more successful bridging the final divide.

The risk of significant disruption in financial markets is not lost on European officials. Negotiations have been contentious, but Greece’s path outside of the Eurozone would be extremely difficult and would involve significant costs from a severe currency devaluation that would make many critical imports unaffordable. Greek banks may only be able to last a few more days in the absence of fresh emergency funding from the ECB, which adds to the pressure to secure a deal.

Although a deal is still possible, a quick resolution is unlikely. Debt relief and a bailout extension is still one realistic path to resolution, at least in the short term. The market may not like that temporary solution, amounting to another instance of “kicking the can down the road” until crisis erupts again, but it is preferable to a chaotic exit from the Eurozone.

BUYING OPPORTUNITY IN EUROPE?

The heightened uncertainty does potentially set up an attractive buying opportunity in Europe. The Eurozone economy has improved (although the Greece crisis may lead to a pause, as discussed in today’s Weekly Economic Commentary), and a potential Grexit is not likely to have meaningful intermediate- or long-term impact on the broader European economy. European equity valuations are relatively attractive when compared with the U.S.

But although the risk of severe market disruption may be low for the reasons discussed above, a chaotic exit from the Eurozone remains a possibility. Even a repeat of the uncertainty seen in the Eurozone in the past few weeks–if it persists for weeks or months–could act as a drag on economic growth. Elections in Spain later this year may be impacted by a possible Greek exit and rise of anti-austerity movements and could lead to renewed contagion fears (as could elections in France and the U.K. in 2017, although those are a long way off). As a result, we would suggest patience. We do not expect a stock market correction (10 - 20% decline) in the U.S. as a result of Greece uncertainty, but that is a possibility in Europe. Market volatility may potentially remain high until we get more clarity in the coming days or weeks.

CONCLUSION

The odds of a Greek exit from the Eurozone are certainly higher following the referendum result, but a deal that keeps Greece in is still possible. Regardless of whether Greece remains in or exits the Eurozone, we expect the risk of contagion to be manageable. Greece is not another Lehman moment. The heightened uncertainty does potentially set up an attractive buying opportunity in European equities, but a chaotic exit for Greece from the Eurozone remains a possibility, even if a low probability outcome, and as a result, we suggest patience. Market volatility may potentially remain high as we await further information on Greece’s path.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Investing in stock includes numerous specific risks including: the fluctuation of dividend, loss of principal and potential illiquidity of the investment in a falling market.

All indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Because of its narrow focus, specialty sector investing, such as healthcare, financials, or energy, will be subject to greater volatility than investing more broadly across many sectors and companies.

Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond and bond mutual fund values and yields will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

Investing in foreign and emerging markets debt securities involves special additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, geopolitical and regulatory risk, and risk associated with varying settlement standards.

Currency risk is a form of risk that arises from the change in price of one currency against another. Whenever investors or companies have assets or business operations across national borders, they face currency risk if their positions are not hedged.

Derivatives involve additional risks, including interest rate risk, credit risk, the risk of improper valuation, and the risk of non-correlation to the relevant instruments they are designed to hedge or to closely track

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

Purchasing Managers’ Indexes (PMI) are economic indicators derived from monthly surveys of private sector companies, and are intended to show the economic health of the manufacturing sector. A PMI of more than 50 indicates expansion in the manufacturing sector, a reading below 50 indicates contraction, and a reading of 50 indicates no change. The two principal producers of PMIs are Markit Group, which conducts PMIs for over 30 countries worldwide, and the Institute for Supply Management (ISM), which conducts PMIs for the U.S.

Quantitative easing (QE) refers to a central bank’s current and/or past programs whereby the bank purchases a set amount of Treasury and/or mortgage-backed securities each month from private banks. This inserts more money in the economy (known as easing), which is intended to encourage economic growth.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC or NCUA/NCUSIF Insured | No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by Any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Tracking #1-398046 (Exp. 07/16)